Introduction

Good afternoon. It’s a great pleasure to be here in Saskatoon, and I want to thank the Saskatchewan Trade and Export Partnership and the Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce for the invitation.

Canada is a trading nation.

We rely on exports for around a third of our income, and we use that income to buy the things we need from abroad. The share of exports in Saskatchewan’s gross domestic product (GDP) is even higher, roughly 45%—that’s the highest in the country. Saskatchewan provides commodities to the world—wheat, canola, potash, oil and gas, uranium and more. And it imports a range of goods, particularly motor vehicles and machinery and equipment, mostly from the United States.

Unfortunately, trade is under attack.

Globally, trade friction has been increasing for the past dozen years, and now the United States has swerved sharply to protectionism. The large increase in US tariffs is weakening global demand, disrupting supply chains, raising prices and putting the Canadian and global economies on permanently lower paths.

These shifts in trade also have implications for international capital flows. Together with unsustainable US fiscal deficits, persistent trade imbalances have the potential to increase financial stability risks globally.

Saskatchewan, like most of Canada, is caught in the crossfire.

New US tariffs on steel, aluminium, motor vehicles, copper and softwood lumber are hurting businesses and affecting workers across the country. But here in Saskatchewan, it’s actually China’s move to effectively block Canadian canola exports into its market that is causing the biggest trade impact.

Around the world, trade is more fragmented, trade with the United States is more difficult, trust is low, and new risks to financial stability are emerging. As an open economy closely integrated with the United States, Canada is particularly affected.

That is what I want to talk about today.

I will begin with a longer-term perspective, outlining four megatrends in global trade and capital flows that are transforming the global economic and financial landscape: Global trade growth has slowed. The United States is no longer the dominant trading nation, but it still dominates global financial flows. And global trade imbalances are widening again. President Trump did not precipitate these megatrends, but his policies will likely reduce trade with the United States further and could dent the US dollar as the global safe asset.

Then I’ll discuss the implications for Canada and the world. For Canada, the ramifications of a new relationship with the United States are immense. And one thing is clear: we can’t afford to wait this out. Canadian leaders—business, political and economic leaders—need to chart a new course. We should have been making these changes 15 years ago. But the next best time is now.

The United States will always be a crucial trade partner. But we need to find new markets for our products and new products for our markets. We need to improve our productivity to compete globally. And we need to attract foreign capital. Around the world, countries and corporations are looking for new partners. Canada should be top of the list.

Shifting global trade and financial flows

With that plan for my remarks, let me begin with the four megatrends.

Global trade growth has slowed

First, global trade growth has slowed. You can see this in Chart 1, which shows global trade as a share of GDP.

In the first 65 years after the Bretton Woods Agreement was signed in 1944, global trade grew faster than the global economy. Open trade brought specialization, innovation and economies of scale. It drove investment and productivity. For consumers, open trade increased selection and lowered prices. Trade spurred income growth across countries, reduced global poverty and raised standards of living.

But since about 2010, trade growth has slowed—it’s no longer growing faster than GDP. Some slowdown was inevitable. Once most economies were participating in open trade, there was less capacity to expand trade further.

Still, part of this slowdown reflects shifting politics. The benefits of open trade have not been evenly shared. When low-cost producers in exporting countries undercut domestic producers, workers who lost their jobs lost more than they gained. This has eroded public and political support for globalization, resulting in a pull-back from open trade.

As a result, trade barriers have been rising for the past dozen years. And now we’re in a new era of US protectionism. US tariffs have not been this high since the early 1930s (Chart 2).

US tariffs are doing two things. They’re reducing bilateral trade with the United States. And they’re rerouting trade as exporters look for ways to get around the tariffs or seek out new partners.

China, in particular, has been ramping up trade with the Global South for several years, and this has accelerated with new US tariffs (Chart 3).

The United States no longer dominates global trade

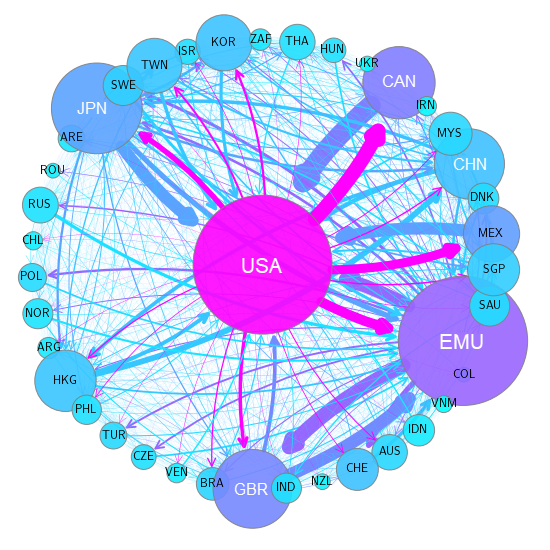

China’s entry to the global trade system and rapid growth over the past 25 years bring us to the second megatrend: the United States no longer dominates global trade. Chart 4 shows trade flows between countries in 2000 and 2019. These charts are courtesy of Hélène Rey at London Business School and her co-authors.

Chart 4: The United States is no longer the hub of global trade

Merchandise trade exports, excluding services

a. 2000

b. 2019

Note: Thank you to Hélène Rey at London Business School for providing these charts. The charts depict the European Economic and Monetary Union instead of the European Union.

Source: S. Miranda-Agrippino, T. Nenova and H. Rey, “Global footprints of monetary policies,” London Centre for Macroeconomics (2020)

The change is dramatic. In 2000, the United States was dominant. Now, the global trading network has three main hubs—China, the United States and the euro area. The global trade network has also become far more complex than it was 20 years ago.

As China expanded its trade, it also moved up the value chain. Twenty years ago, advanced economies were happy to buy low-tech consumer goods produced by state capitalism in China. Prices were low, which benefited US consumers. But now China is competing head-to-head with the United States and other countries in advanced manufacturing and high tech.

The global trade system is designed for private companies competing in an open marketplace. But in China, trade is being used as an instrument of state-directed growth that gives Chinese companies an advantage over their competitors. In response, advanced countries have increasingly embraced industrial policy across a widening spectrum of strategic industries.

China’s ascendence and use of industrial policy have also spurred the swerve in US trade policy. US tariffs on Chinese goods peaked in April at about 150%. Since then, tensions have de-escalated considerably. But the effective tariff rate on China remains high, at about 40%, and both countries have imposed export restrictions on some strategically important products.

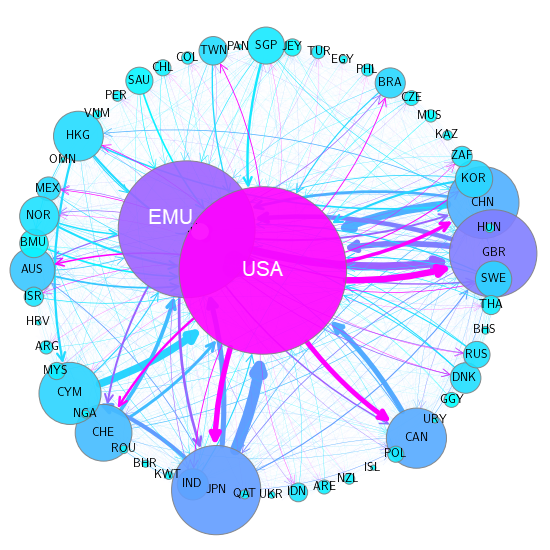

The United States still dominates financial flows

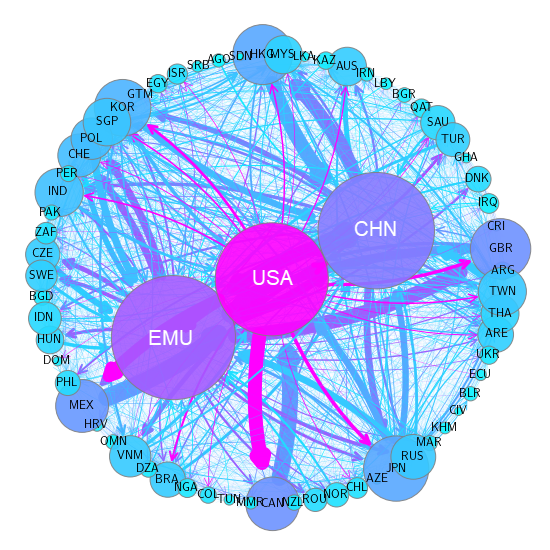

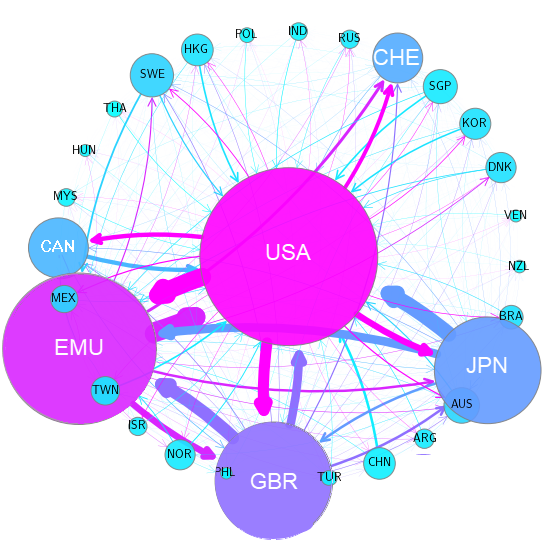

This brings me to the third megatrend. While the United States no longer dominates trade, it continues to dominate global financial flows (Chart 5).

Chart 5: The United States is still the hub of global financial flows

Portfolio assets, includes private and official cross-border investments in equity and debt securities

a. 2000

b. 2018

Note: Thank you to Hélène Rey at London Business School for providing these charts. The charts depict the European Economic and Monetary Union instead of the European Union.

Source: S. Miranda-Agrippino, T. Nenova and H. Rey, “Global footprints of monetary policies,” London Centre for Macroeconomics (2020)

The United States has the biggest equity and debt markets. The size and dynamism of the US stock market fuel growth companies. The depth and liquidity of the US Treasury market, along with very low perceived credit risk, have made US Treasury bills the global risk-free asset. This has increased demand for US dollars and made the US dollar the global reserve currency.

Providing safe assets to the world has its benefits. The United States can borrow money to finance growing fiscal deficits at a lower rate than it could otherwise.

For many global investors, the question now is whether US dominance in global financial flows will ebb as the United States pulls back from trade and runs large fiscal deficits.

The recent performance of the US dollar may be telling us something. Typically, we’d expect US tariffs to support the US currency. But, instead, the greenback has depreciated, and the price of gold—another safe asset—has risen. President Trump’s “Liberation Day” shook global confidence, and the dollar’s safe-haven role was called into question. Stock markets have since recovered, but the dollar has depreciated by about 10% against other major currencies since the start of the year, and the price of gold is up over 40%.

It’s too early to know if this is the start of a new era. For now, the greenback remains dominant, and—without a clear alternative—I suspect it will remain the global reserve currency for the foreseeable future. But for many, its value as a hedge in times of stress has been dented. And President Trump’s attempts to influence the Federal Reserve are raising questions about the continued independence of US monetary policy.

Global imbalances persist

The final megatrend I want to touch on is the persistence of global imbalances.1 By this I’m referring to the persistent trade deficit in the United States and the large and continuing surpluses elsewhere, especially in China and the European Union (Chart 6).

International capital flows are the flip side of trade imbalances.

To fund its trade deficit, the United States relies on net capital inflows—foreigners purchasing US debt and equity—as well as foreign direct investment. In other words, the United States must attract savings from abroad because it does not save enough at home. In contrast, China and the European Union both have excess savings.

Domestic factors are the main reason for the widening of imbalances between these major economies. China’s consumption has been persistently weak. Households in China hold high precautionary savings because social safety nets are not well developed, and the property sector has been shaky. In the European Union, investment has been weak relative to savings because opportunities are less attractive, especially in high tech.

The opposite is true in the United States. Consumption and investment are high, fiscal deficits are large, and the savings rate is low. So the United States is running a trade deficit, and the biggest counterparts are the European Union and China.

Imbalances are not inherently bad—global capital flows are part of a well-functioning international trade and financial system. But risks accumulate when the imbalances grow unsustainably and the necessary adjustments do not take place.

Countries or regions with a trade surplus—in this case, China and the European Union—generally face little market pressure to adjust. Usually, most of the adjustment would be forced onto the country with a trade deficit—the United States. But because the US dollar is the global reserve currency, foreign investors have been willing to finance US spending. So imbalances persist.

Why do we care? Because we’ve seen it go wrong before. In the lead-up to the 2008–09 global financial crisis, imbalances built up as China ran large trade surpluses and the United States ran large trade deficits. The US subprime mortgage implosion was a product of flawed financial innovation and lax regulation. But the massive inflows of foreign capital to the United States made a local problem global—and they sparked the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Global imbalances narrowed after the crisis, but they’ve started to grow again. Because of insufficient domestic savings, the US fiscal deficit must be funded in part by foreign investors, and they could become less enthusiastic about US assets. At the same time, US government debt is increasingly being purchased by non-bank financial intermediaries, particularly hedge funds using highly leveraged strategies. This is increasing leverage at the very core of the financial system. These are vulnerabilities.

And, no, US tariffs probably won’t fix global imbalances. Lower US imports from the rest of the world will likely come at the cost of lower US exports. As long as the United States is spending more than it’s producing, it needs to import more than it exports.

The shifts have global implications

These megatrends have global implications. And now new US tariffs combined with the unpredictability of US policy are increasing uncertainty, shifting relationships, weakening global demand and reducing the efficiency of global supply.

Countries around the world are adjusting their supply chains and seeking out new partners. China’s reach into emerging-market economies is increasing. New partnerships support China’s quest for a multipolar world, where the United States has less geopolitical weight. The European Union, too, is making changes—beyond simply diversifying trade—by tackling internal challenges that have hampered its competitiveness.

The global economic fallout from the US trade war has so far been milder than first predicted—both because US tariffs are not as high as initially feared and because retaliatory tariffs were limited. But the full impact has yet to be seen. Many US households remain cautious about spending, and US employment growth has slowed. In the euro zone, growth looks to be softening as US tariffs weaken exports. In China, export substitution to Asian markets has offset the worst effects of US tariffs so far. However, businesses are investing less, and growth is expected to slow.

What can governments around the world do? When the United States raised tariffs sharply in the 1930s with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, most leading nations responded by erecting their own trade barriers. The combined impact was severe, contributing to the depth and persistence of the Great Depression. This time, countries have avoided an escalating global trade war. That’s good, but they could go further by strengthening trade ties where possible.

The era of open trade with the United States may be over, but the rest of us can still deepen trade with others. To do this, we will need our multilateral institutions—particularly the World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—to work together better to address the problems of unbalanced trade and the lack of adjustment.

Together, countries also need to be prepared for new financial stability risks. We need financial supervisors to strengthen surveillance of financial vulnerabilities—especially as hedge funds and other non-bank financial intermediaries play an increasingly important role in the financial system. Here the IMF and the Financial Stability Board need to work together to identify potential systemic risks.

For their part, businesses need to consider both geopolitical risks and the resilience of supply chains along with efficiency. More industrial policy means chief executive officers need to think about how their corporate strategies interact with national priorities. These national priorities may allow businesses to take more risks to fuel growth, but they should not be used to create monopolies.

Central banks also have a role to play, but it is limited. Monetary policy cannot undo the damage caused by tariffs. At best, monetary policy can smooth the path in the short term, supporting economic growth while ensuring inflation is well controlled.

What it all means for Canada

This brings me to the impact and implications here at home—in both the short term and the longer term.

The tariff shock is hurting economic growth and employment

First, the near term. Trade growth in Canada had slowed well before the re-election of President Trump: trade as a share of GDP stopped increasing in about 2000.

But Canadian exports have declined sharply since President Trump imposed new tariffs on Canada and created considerable uncertainty with tariff threats and reversals. The pain is falling primarily on a few key sectors: steel and aluminium and motor vehicles. Last month, tariffs were increased or extended to more goods, including copper and softwood lumber. High tariffs are also being imposed on exports that are not compliant with the Canada-US-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). While most of Saskatchewan’s exports comply with CUSMA and are not affected by US tariffs—at least not directly—the hit from China’s tariffs on canola is significant.

The economic impact has been a whipsaw: Growth held up at the start of the year as exporters shipped all they could to get ahead of the tariffs. This reversed in the second quarter—exports dropped almost 27% and GDP contracted by 1.6%.

The sharp drop in exports is hurting the job market. The unemployment rate rose from 6.6% in February to 7.1% in August. Hiring and employment in trade-affected sectors are down sharply, and employment growth in the rest of the economy has slowed. Many businesses have also told us they have paused investment plans given elevated uncertainty about US trade policy.

Canada’s long-term prosperity requires change

In the longer term, increased trade friction with the United States means our economy will work less efficiently, with added costs and less income.

Chart 7 shows the Bank of Canada’s assessment of the growth path for the Canadian economy before US tariffs—the blue line—and with US tariffs based on trade policy as of the end of July—that’s the orange line. We can see that the orange line is permanently below the blue line. Monetary policy cannot undo the efficiency costs of US tariffs—it can’t bend the orange line back up to the blue no-tariff line. Nor can counter-cyclical fiscal stimulus.

But positive structural reform could.

Canada has a choice. We can live with the structural impact of a more protectionist United States—the lower path. Or we can improve our productivity and competitiveness and bend the orange line back up to, or even above, the blue line.

Canadians have embraced the power of economic patriotism—elbows up. But now we need to roll up our sleeves and do the hard work to be more competitive.

We need to diversify our trade by growing our internal market and finding new overseas markets. And we need to improve our productivity and make ourselves more attractive to investors. That work has started, and I’ve spoken about all these things before, so let me be brief but clear.

There are some things we could do quickly at little fiscal cost—if we have the determination. There is momentum to eliminate interprovincial trade barriers. We need to take a comprehensive approach that lowers the cost of doing business across the country. This includes removing trade barriers and many small regulatory differences. It also includes mutually recognizing provincial labour accreditation for many professions. We also need to remove unintended barriers to investment by shortening regulatory approvals and reducing regulatory uncertainty.

Then there are other things that require investment and will take time to build, but the sooner we start, the sooner we will reap the benefits. Here I would include better east–west transportation links to grow our internal market and get our products to overseas markets. I’d also include new port capacity to reduce our dependence on the United States.

If we can get our products overseas, we have some of the best market access in the world. Canada has trade agreements with 50 countries beyond the United States. But businesses and governments could do more to leverage these agreements. We need to learn from the past: the recession in 2009 highlighted how vulnerable we are to a drop in US demand, and everyone talked about diversification then, too. But not much happened. This time we need to follow through.

Finally, we also need to nurture and support our long-standing strengths. We have the ingredients to attract more foreign capital. We have effective governments and rule of law. We have abundant energy and other resources. We have a diversified industrial structure. We have strong labour force participation, a good immigration system and broad access to quality education. But our immigration system has been strained, and our universities and colleges are facing a financial squeeze. We can’t take our strengths for granted.

Increasing productivity and improving our competitiveness may not be every Canadians’ biggest priority. But if we can bend the orange line back up to or above the blue line, everything from housing to health care becomes more affordable. Productivity growth is what sustains increases in our standard of living.

Conclusion

I need to wrap up.

But before I do, let me return to the role of monetary policy in all this. Tariffs have weakened our exports and GDP growth, slowed the job market and added costs. Monetary policy cannot undo the damage caused by tariffs, but it has a role to play supporting the economy through this period of adjustment while maintaining price stability. Last week, the Bank lowered its policy interest rate to better balance the risks we face as the economy adjusts to a new trade relationship with the United States. We are proceeding carefully with particular attention to the risks and uncertainties. And as we demonstrated last week, we are prepared to respond to new information. We will support economic growth while ensuring inflation remains well controlled.

But as we all deal with the immediate fallout of global fragmentation and rising protectionism, business leaders and policy-makers alike need to think about the deeper structural weaknesses that threaten the resilience of the Canadian economy. There is no better time than now to deepen investment, improve productivity and expand our market.

We have the capacity to overcome the negative impact of new trade restrictions with the United States. Elbows up has been galvanizing, but now we need to roll up our sleeves. There is a lot of hard work to do.

I would like to thank Daniel de Munnik, Tuuli McCully, Olena Senyuta and Ben Tomlin for their help in preparing this speech.

Related Information

Speech: Saskatchewan Trade and Export Partnership and the Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce

Global trade and capital flows — Governor Tiff Macklem speaks before the Saskatchewan Trade and Export Partnership and the Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce. (14:30 (ET) approx.).

Media Availability: Saskatchewan Trade and Export Partnership and the Greater Saskatoon Chamber of Commerce

Global trade and capital flows — Governor Tiff Macklem takes questions from reporters following his remarks (15:45 (ET) approx.).