Browse previous versions of the Financial System Review.

- In the Financial System Review (FSR), the Bank analyzes the resilience of the Canadian financial system. The first section of the FSR summarizes the judgment of the Bank of Canada’s Governing Council on the main vulnerabilities and risks to financial stability. It also highlights the efforts of authorities to mitigate those risks.

- Financial and macroeconomic stability are interrelated. The FSR’s assessment of financial risks is therefore presented in the context of the Bank’s assessment of macroeconomic conditions, as given in its Monetary Policy Report.

- The FSR also presents staff analysis of the financial system and policies to support its resilience. More generally, the FSR promotes informed discussion on all aspects of the financial system.

Introduction

Elevated household indebtedness, housing market imbalances and the potential for cyber attacks to disrupt the highly interconnected financial system remain the key vulnerabilities affecting the Canadian financial system. While there are some continued signs of easing, household vulnerabilities remain elevated and are expected to persist for some time.

The Canadian economy is operating close to its potential. Labour income growth is solid, supporting households’ ability to service their outstanding debt, albeit in an environment of rising global interest rates.

As anticipated in the November 2017 Financial System Review (FSR), monetary, macroprudential and other policy measures have led to a slowing in household credit growth and have moderated activity in the housing market. Tightened mortgage standards are also improving the quality of new mortgage lending, leading to fewer households becoming highly indebted. Although the market for single-family homes in Toronto has cooled, imbalances in condominium markets have continued to grow, particularly in Vancouver and Toronto and their surrounding regions.

Cyber attacks and other operational-risk incidents could seriously disrupt the financial system if they propagated widely or undermined confidence. Collective actions to improve cyber defences and recovery planning will help reduce the potential impact of such incidents.

The overall risk to the financial system is broadly unchanged since November 2017. Elevated financial vulnerabilities have the potential to amplify the effects of adverse shocks on the economy and the financial system. But the Canadian financial system is resilient, and its ability to manage negative shocks is being further improved by new policy measures.

Macrofinancial conditions

Solid economic growth has led interest rates in Canada and some other advanced economies to rise from historically low levels (Chart 1). Over the past year, yields on US five-year sovereign bonds have risen by as much as 119 basis points and are currently about 95 basis points higher than a year ago. Sovereign yields in Canada have risen by a similar amount, contributing to higher bank funding costs.

Consequently, five-year fixed mortgage rates have increased by about 110 basis points, while rates for new variable mortgages rose by close to 40 basis points. Since the implementation of new mortgage standards, non-price lending conditions for mortgages and home equity lines of credit have also tightened.

Equity volatility has returned to its post-crisis average after a sharp repricing in February. Some risk premiums have also begun to edge up, partly due to geopolitical developments. In addition, financial stress is developing in some emerging-market economies (EMEs), particularly those with high levels of foreign currency debt and weaker current account positions. However, asset valuations are still elevated and risk premiums remain at low levels across a number of asset classes, including bonds (Chart 2).

Notes: The excess bond premium captures compensation for risk beyond expected default and provides a measure of investor sentiment or risk preference in the corporate bond market. The term premium is the estimated term-structure risk-premium component from yields on 10-year zero-coupon government bonds.

Sources: Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Bloomberg Finance L.P. and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: May 2018

Key vulnerabilities in the Canadian financial system

Vulnerability 1: Elevated level of Canadian household indebtedness

Strong income gains, a significant slowing in household credit growth and improvements in credit quality have begun to ease the vulnerability associated with high household indebtedness. But even as conditions slowly improve, the sheer size of the outstanding debt means that the vulnerability will likely persist at an elevated level for some time.

As expected, higher interest rates and policy measures related to mortgage financing and housing are restraining credit growth. The quality of new mortgage debt has continued to improve because of tightened mortgage underwriting standards. However, it is too early to assess the full effects of the most recent changes on new lending, including the volume of credit activity migrating to credit unions and private lenders. Higher overall debt levels make existing mortgage holders more sensitive to interest rate increases. The pace of rate increases will depend on domestic monetary policy and global market forces. The ability of households to manage payment increases associated with higher rates will also depend on the pace of income growth.

The ratio of household debt to disposable income was near 170 per cent at the end of 2017 and is likely to have declined slightly in the first quarter of 2018. Growth in residential mortgages and home equity lines of credit slowed in the first four months of the year, in line with weaker home sales and slower house price growth (Chart 3 and Vulnerability 2). The pace of other consumer borrowing, which makes up the remaining 15 per cent of outstanding household debt, has also slowed.

Auto loans, which represent around 40 per cent of this other consumer credit, grew by 5.5 per cent in 2017. Households have been taking longer to pay down their auto loans. As a result, car values often depreciate faster than loan principals: around one-third of consumers trading in their old car for a new one owe more than their old car is worth.1 High auto debt would be more of a concern if loans were increasingly going to riskier, non-prime borrowers, or if borrowers were experiencing difficulties making payments. But the share of loans going to non-prime borrowers has remained stable, at roughly 22 per cent.2 The rate of non-prime auto loans falling into payment arrears also remains modest, with only a slight increase from 0.7 to 0.9 per cent over 2017.

Chart 3: Household credit growth slowed in recent months

Note: Growth rates in credit are in three-month seasonally adjusted annualized terms. The consumer credit

series excludes one-off events, such as the reclassification of institutions between sectors. The November

FSR line is placed to indicate the most recent data available at the time of the report, not the publication date.

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observations: credit series, April 2018;

debt-to-disposable-income, 2017Q4

Tightened mortgage underwriting standards have reduced the maximum size of loans that borrowers can obtain at a given level of income (Box 1). In the autumn of 2016, changes to mortgage insurance rules made all high-ratio mortgages (those with a loan-to-value ratio above 80 per cent) subject to a mortgage interest rate stress test. This requirement cut in half the proportion of new high-ratio borrowers who take on mortgage debt in excess of 450 per cent of their gross income (Chart 4). Looking at total mortgages, the share of these highly indebted households in new mortgage lending stopped rising and even declined slightly beginning in late 2017. The 2016 changes have also led to a reduction in the proportion of new low-ratio mortgages with an amortization period longer than 25 years.3

The updated Guideline B-20, which took effect at the beginning of 2018, tightened standards for low-ratio mortgages.4 The guideline is dampening credit growth and improving the quality of new mortgage lending, especially in regions with the highest house prices. For example, because of the new mortgage interest rate stress test, the size of a 5-year, fixed-rate mortgage with a 25-year amortization that a median-income borrower in Canada can qualify for dropped by about $82,000 to $373,000 (Box 1). The stress test will have more significant effects in markets such as the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and Greater Vancouver Area (GVA), where house prices are higher relative to incomes and low-ratio mortgages are more common.

Due to transitional factors, it is too early to observe the full effects of the updated Guideline B-20 in data on low-ratio mortgages used for purchases. Some borrowers who were concerned that they would not qualify under the new guideline likely chose to advance their borrowing decisions and took out loans near the end of 2017. As well, some of the mortgages that originated in the first quarter of 2018 had already been pre-approved under the old guideline. As a result, the share of highly indebted borrowers in new mortgages used for purchases dropped only slightly in the first quarter.

The low-ratio data also include mortgage refinancing transactions, which are less likely to have been affected by these transitory factors. Therefore, a higher portion of refinancing loans were probably approved under the new guideline. Among refinances, the share of highly indebted households dropped by around 2.5 percentage points in the first quarter. This suggests that a larger decline in the share of these borrowers in purchases should be evident once pre-approvals from 2017 have expired.

Table 1 shows some of the data sources the Bank of Canada uses to monitor the mortgage market. It indicates when data will be available for the second quarter of 2018. From the second quarter onward, data will be less affected by transitional factors.

The updated Guideline B-20 is expected to weigh on economic activity, subtracting about 0.2 per cent from the level of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of 2019. Considerable uncertainty around its ultimate impact on economic activity and mortgage quality remains, since the effects depend not only on how borrowers and lenders choose to adapt to the new conditions, but also on other developments in housing markets and the broader economy.

Box 1: Mortgage interest rate stress tests

Canadian financial institutions generally have robust underwriting practices for mortgages. More recently, federally mandated mortgage interest rate stress tests were introduced to help ensure that borrowers can adjust to future increases in their mortgage rates.

To qualify for a mortgage, borrowers typically need to demonstrate that their debt payments and other housing-related costs will not account for too large a share of their income. A borrower’s ability to pay is assessed by calculating a debt-service ratio and comparing it with a maximum allowable value.5 To meet the stress test, a borrower’s debt-service ratio is calculated using a higher mortgage rate than the rate the lender will charge. The stress test affects only the maximum loan that a borrower can qualify for at a given level of income; it does not change the size of the borrower’s payments. Table 1-A provides an example of how the stress test constrains mortgage size.6

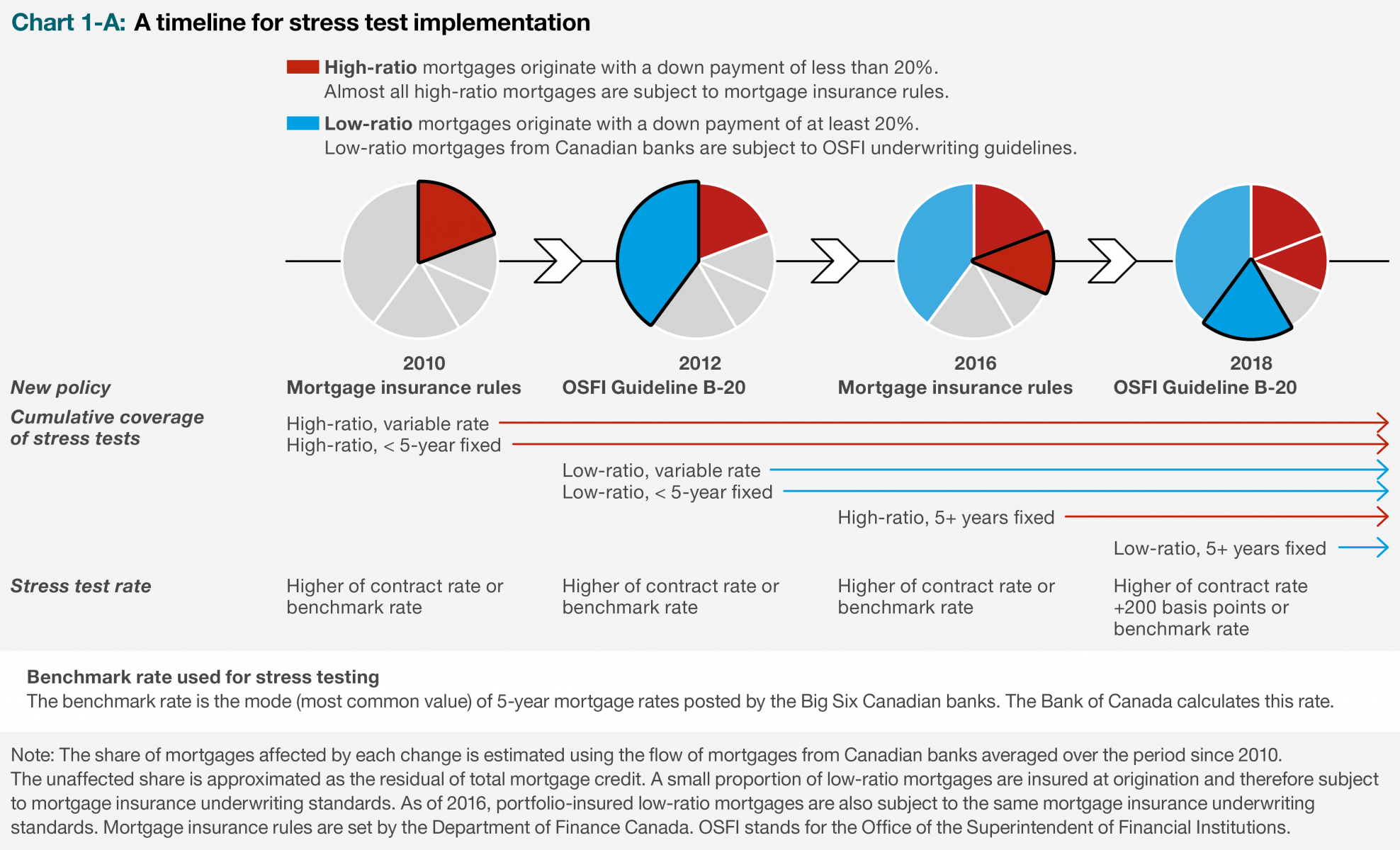

Before 2016, federally mandated stress tests applied only to mortgages with variable rates or with fixed terms of less than five years. Starting in the autumn of 2016, federal authorities extended stress tests to cover almost all mortgages—first through changes to mortgage insurance rules and then through an updated mortgage underwriting guideline for banks (Chart 1-A).

Banks can make some exceptions to provide low-ratio loans to borrowers with high housing equity or financial wealth. In addition, the federally mandated stress tests do not extend to mortgages from non-federally regulated lenders unless those loans are subject to mortgage insurance rules.

Table 1-A: Effects of the mortgage interest rate stress test

| Example for a median-income borrower | ||

|---|---|---|

| No stress test | With Guideline B-20 stress test | |

| Household income | $98,000 | $98,000 |

| Mortgage type | Uninsured, 5-year, fixed-rate, 25-year amortization period | |

| Qualifying rate | 3.69% | 5.69% |

| Maximum loan size | $455,000 | $373,000 |

| Maximum loan-to-income ratio | 465% | 380% |

Note: The income and the non-mortgage debt-service expense used in these calculations are based on the median characteristics of mortgage borrowers nationally in 2017. The qualifying rate in the “no-stress-test” example is based on prevailing five-year fixed mortgage rates for low-ratio mortgages from national mortgage brokers. Thresholds for the gross debt-service ratio and total debt-service ratio of 39 per cent and 44 per cent, respectively, are applied, although individual lenders can set their own thresholds.

Chart 4: Fewer mortgages are going to highly indebted borrowers

Note: Data include purchases and refinances originated by federally regulated financial institutions. For

high-ratio mortgages, the share with high loan-to-income ratios is larger than in previous issues of the FSR

because the mortgage insurance premium is now included in the loan amount. The November FSR line is

placed to indicate the most recent data available at the time of the report, not the publication date.

Sources: Department of Finance Canada, regulatory filings of Canadian banks and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: 2018Q1

Table 1: A variety of data sources is required to assess the quality of lending

| Source | Type of data | Coverage | Date 2018Q2 data are available |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory filings of Canadian banks | Loan-level data describing the characteristics of mortgage originations and renewals, including household income and asset values | Federally regulated lenders | September |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation | Aggregate and loan-level data similar to regulatory filings of Canadian banks | Participants in government securitization programs, including credit unions | Late 2018 |

| Teranet | Land registry data from Ontario, including loan sizes, property values and interest rates | All mortgage lenders in Ontario, including private lenders | July |

| TransUnion | Anonymized household credit data on outstanding loans and payment histories | Most Canadian lenders | September |

Borrowers who want a larger loan than they qualify for under Guideline B-20 may seek out other lenders, such as credit unions and private lenders, who are not always subject to federal mortgage standards. This could make the new guideline less effective in mitigating the vulnerability for the financial system as a whole.

Credit unions are regulated under provincial rules, and only their insured mortgages are subject to federally mandated stress tests. Among provincial authorities, so far only the Quebec Autorité des marchés financiers requires caisses populaires to apply an equivalent mortgage interest rate stress test. Elsewhere, some credit unions are voluntarily using stress tests similar to those mandated in the federal standards.

Borrowers could also turn to less-regulated private mortgage lenders, such as mortgage investment companies. In 2015 and 2016, the volume of new private lending in the GTA increased in line with overall growth in the market.7 Since 2017, the volume of private lending has been relatively stable, at a little more than $2 billion per quarter (Chart 5), while other sources of lending have declined. The market share of private lending has therefore climbed to nearly 8 per cent of new mortgages in the GTA. This share overstates the importance of private lenders, however, because their loans have shorter terms compared with those of other lenders. As discussed in the November 2017 FSR, to increase their activity substantially, private lenders would need to further develop their lending channels and operational capabilities, and, most importantly, they would have to materially expand their funding sources.

Forthcoming data for the second quarter will help improve understanding of the extent of potential movement to non-federally regulated lenders (Table 1). Some of the data will come from the approved issuer data reporting framework recently established by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The framework will help monitor mortgage underwriting practices.

Chart 5: In the Greater Toronto Area, the volume of private lending has been stable for the past year

Note: Originations include purchases, refinances and second mortgages. Mortgage finance companies are not considered private lenders. Volume is seasonally adjusted.

Sources: Teranet and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: 2018Q1

Higher levels of debt mean that interest rate increases will have a larger effect on households’ financial positions and consumption spending than they had in the past.8 Existing borrowers are affected by interest rate increases when their mortgage comes up for renewal if it has a fixed rate or immediately if their mortgage has a variable rate.9 With variable-rate and renewals of fixed-rate mortgages combined, just under half of existing mortgage holders in any given year (or a little more than half if home equity lines of credit are included) are affected by rate increases.10 The proportion of mortgage borrowers subject to interest rate risk each year has been relatively constant over the past six years.

Most existing mortgage holders have not borrowed the maximum amount they can obtain and therefore likely have some room to manage higher mortgage payments. In addition, households with variable-rate mortgages or fixed-rate mortgages with terms of less than five years have already been subject to a stress test (Box 1). Because they passed the test, they should be able to manage somewhat higher interest rates. The exception would be households that have experienced declines in income or substantially increased their other borrowing since qualifying for their mortgage.

Around 45 per cent of outstanding mortgages are five-year, fixed-rate mortgages and roughly 20 per cent of these come up for renewal each year. Homeowners with these mortgages were not subject to stress tests until recently, and some of them may have difficulty managing an increase in payments when they renew their mortgages. The effect of an interest rate increase on these households will depend on the level of their debt and income.

For illustration purposes, assume that the mortgage rates of borrowers renewing in 2019 are 100 basis points higher than the rates they paid at origination in 2014.11 Assume also that, in 2020, rates for renewers are 200 basis points higher than the rates they paid at origination in 2015. To assess how this will affect households whose income stays constant, consider the size of mortgage payments relative to income—the debt-service ratio (DSR). In 2019, more than 90 per cent of the five-year fixed-rate borrowers would face increases in their DSR of less than 3 percentage points (Table 2). In 2020, when borrowers face a larger hypothetical interest rate increase, 46 per cent of borrowers would have increases in their DSR of less than 3 percentage points and close to 20 per cent of borrowers would have increases in their DSR exceeding 5 percentage points.

However, in the time between when these borrowers took out their mortgage and when they renew, many will likely be earning a higher income. Over the past five years, nominal labour income for the average Canadian worker has cumulatively increased by about 11 per cent. Income growth will nevertheless vary across individual households. Those who experience smaller income gains will have more difficulty making the higher mortgage payments, especially households that have high debt relative to income.

Table 2: Potential increase in housing debt-service ratios at renewal

| Percentage of five-year fixed-rate mortgage borrowers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renewal year | Hypothetical mortgage rate increase at renewal | Increase in debt-service ratio between origination and renewal, assuming no increase in nominal income | |||

| <1 pps | 1–3 pps | 3–5 pps | >5 pps | ||

| 2019 | +100 basis points | 27% | 67% | 6% | 0% |

| 2020 | +200 basis points | 9% | 37% | 35% | 19% |

Note: Calculations include purchases and refinances. The debt-service ratio is the ratio of mortgage payments to pre-tax income. Amortization remains constant. pps = percentage points

Sources: Regulatory filings of Canadian banks and Bank of Canada calculations

Vulnerability 2: Imbalances in the Canadian housing market

Led by strength in Toronto and Vancouver and their surrounding areas, the average home price in Canada has risen significantly in recent years.12 Over the past year, however, declining affordability, together with monetary, macroprudential and housing policy measures, has weighed on housing markets. As a result, growth in the average home price in Canada has slowed sharply, led by declines in the price of homes in the GTA.

In Toronto and Vancouver and their surrounding areas, the market for single-family homes has cooled, while condominium prices have continued to grow at a rapid pace. Economic fundamentals are driving these changes, but speculative activity may also be supporting strong price gains in condominiums.

Overall, the vulnerability associated with imbalances in the Canadian housing market shows some signs of lessening but remains elevated.

House price growth in Canada was strong for several years, peaking in early 2017. Employment gains, increased immigration and low interest rates have boosted demand, while geographic constraints and land-use regulations have limited the supply of new single-family homes, particularly in some of Canada’s large urban centres. Speculative behaviour also contributed to higher prices in some key markets, as have higher building fees and taxes.13

Since last year, however, declining affordability, tighter mortgage underwriting standards and higher interest rates have weighed on housing demand and price growth, especially for more expensive homes. Taxes on non-residents have also dampened demand and overall market sentiment. Foreign buyer activity in the Greater Golden Horseshoe has been lower since the Ontario Fair Housing Plan was implemented in April 2017.14 In February 2018, British Columbia raised its foreign buyers’ tax from 15 per cent to 20 per cent and expanded the coverage to some areas outside of Vancouver.15 From the strong levels observed in early 2017, national resales are declining on a year-over-year basis. Going forward, solid labour income growth and immigration should support a pickup in housing activity.

Overall, growth in national house prices is down from its peak of just under 20 per cent on a year-over-year basis in April 2017 to about 1.5 per cent one year later. Slower national price growth was driven by price declines in the GTA and its surrounding areas (Chart 6). In the GVA and nearby areas, the rebound in price growth that began in mid-2017 has started to reverse amid fewer resales.

Housing markets in energy-producing regions remain soft. In Calgary, for example, house prices have been stable after recovering from the 2014–15 oil price shock. Sales are down considerably from last year, however, while active listings are rising.

In contrast, prices in some other housing markets, such as Montréal, have remained on a modest upward trajectory. In these markets, the recent momentum has followed years of relative price stability.

Chart 6: Toronto-area prices have continued to slow national house price growth

Note: The lines represent averages of quality-adjusted prices weighted by the population of the corresponding

census metropolitan areas as defined by Statistics Canada. The November FSR line is placed to indicate the

most recent data available at the time of the report, not the publication date.

Sources: Canadian Real Estate Association, Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: April 2018

Between 2012 and 2017, increases in the prices of single-family homes outpaced the prices of condominiums, with supply constraints playing an important role (Chart 7). In fact, neighbourhoods in Vancouver and Toronto with the least construction of new single-family homes recorded the largest price gains.

Since 2017, however, the trend has reversed, driven mainly by changes in the Toronto and Vancouver areas. High prices for single-family homes and recent policy changes have led to a shift in demand away from single-family homes to less-expensive dwellings, including condominiums. As a result, growth in the prices of single-family homes has slowed markedly (Chart 8). In the GTA, single-family house prices have returned to early 2017 levels. Market sentiment deteriorated, reducing investor demand and exacerbating the fall in the prices of single-family homes (Chart 9).

Condominium prices have grown rapidly in the GTA and the GVA (Chart 8). Growth in condominium prices in cities surrounding the GVA has been especially strong, with increases reaching 30 per cent in Victoria and 60 per cent in the Fraser Valley on a three-month annualized basis.

Completed and unsold condominium inventories remain low in both the GTA and the GVA due, in part, to persistent construction delays.16,17 Nonetheless, the number of condominiums under construction is at or near record highs in both cities, suggesting that it may be difficult to sustain the recent pace of price gains over the longer term.

There is also evidence that speculative activity may be supporting the growth in condominium prices in the resale market. An analysis by the Toronto real estate firm Realosophy found an upswing in activity by investors who were buying condominiums and then renting them out within the same year.18 This greater activity—even as carrying costs (including mortgage payments, property taxes and maintenance fees) have increasingly exceeded rental revenue—suggests that investors have been counting on a continuation of large price increases. Prices that are inflated because of these types of expectations tend to be more sensitive to adverse shocks. If expectations reverse and prices recede, speculators may quickly sell their assets, which could lead to large, rapid price declines, with adverse consequences for the rest of the market.

Chart 7: Prices for single-family homes grew faster than condominium prices in Canada until early 2017

Sources: Canadian Real Estate Association and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: April 2018

Chart 8: Markets for single-family homes in the Toronto and Vancouver areas have softened

Sources: Canadian Real Estate Association and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: April 2018

Chart 9: House prices declined the most in Toronto neighbourhoods where investor presence was the largest

Note: The share of investors is calculated as the percentage of freehold homes sold through the Multiple Listing Service that were immediately listed for rent through the same system. House price growth is for

quality-adjusted benchmark prices of single detached homes.

Sources: Realosophy Realty Inc., Toronto Real Estate Board

and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: April 2018

Vulnerability 3: Cyber threats, operational risks and financial interconnections

A successful cyber attack or other operational incident at a financial institution or market infrastructure that propagates across the financial system could interrupt the delivery of crucial financial services. The interconnections that make this possible are a structural feature of the financial system and are essential to its efficient functioning. But these interconnections also mean that cyber attacks and other operational incidents extend beyond the concern of any single entity. Ongoing collaboration among public and private stakeholders is therefore crucial for addressing evolving cyber and operational vulnerabilities.

Attempted cyber attacks are frequent and come from a variety of sources. Financial institutions have made significant investments in capabilities for defending against attacks, as well as for identifying and containing successful breaches. If the breach is not contained, a successful cyber attack could affect the broader financial system through direct or indirect links. A successful attack could also undermine confidence in the financial system. For example, concerns about the integrity of financial data, including its destruction or modification, could affect confidence.

Sophisticated attack tools are becoming more widely available as attackers collaborate to increase their capabilities. At the same time, growing demand for skilled cyber security personnel is outstripping supply. To combat this, financial institutions and authorities are building collaborative responses to potential threats. A greater pooling of defensive resources increases the overall protection of the system.

Even as defensive capacity improves across the financial system, some attacks will inevitably succeed. Having strong recovery plans can help to quickly restore financial system functioning and prevent a loss in confidence. For the Bank, this means both augmenting its own cyber defences and investing in operational redundancies.19

The Bank is also responsible for overseeing payment clearing and settlement systems. For example, it ensures that appropriate cyber security tools and practices are in place at systemically important financial market infrastructures. Beyond reinforcing the infrastructures themselves, the Bank is collaborating with the Big Six Canadian banks and Payments Canada to create a collaborative plan for a rapid recovery should a key participant in the wholesale payments system be affected by a serious cyber security event.20

Since cyber threats cut across mandates, jurisdictions and borders, the Bank continues to collaborate domestically and internationally. The Bank is working closely with our partners to implement the new National Cyber Security Strategy recently announced by the federal government. The Bank participates in the G7 Cyber Expert Group, as well as the SWIFT Global Oversight College and groups organized by the Bank for International Settlements. In May 2018, the governors of major central banks endorsed the strategy adopted by the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures to reduce the risk of fraud in wholesale payments. The strategy proposes to go beyond the system operators to focus on the banks, financial market infrastructures and other financial institutions that are participants in wholesale payment systems.21

Other vulnerabilities

Beyond the key vulnerabilities discussed above, the Bank monitors and assesses other vulnerabilities across the entire financial system, including those related to financial institutions, markets and non-bank credit intermediation. This section highlights a few specific areas that have been the focus of recent attention. Although these are not considered key vulnerabilities, the Bank continues to examine data and develop new analysis as part of its ongoing monitoring.

Some small and medium-sized banks focus on uninsured mortgage lending, often to non-traditional borrowers. A significant proportion of funding for these monoline banks has come from brokered deposits—bank deposits placed by third parties. Most brokered deposits are sourced through investment dealers owned by large banks. The experience of Home Capital in 2017 was a reminder that brokered deposits can be withdrawn more quickly than traditional deposits, even though both carry deposit insurance.22 A few monoline banks have launched online deposit-taking platforms to diversify their deposit base and to reach retail depositors directly rather than through brokers.

The funding profile of these banks will continue to be closely monitored. Although these institutions are small, concerns associated with one could spread to other, similar institutions and possibly to the wider banking system. This underscores the need to further develop more stable funding sources for mortgage lending. Covered bond programs might be able to fulfill part of that need, but they are not currently economical for small banks.23 Another option is private-label residential mortgage-backed securities.24

Access to global financial markets can help strengthen banks’ funding profiles. Foreign funding allows banks to diversify their funding sources and, in many instances, obtain lower-cost funding. It also allows banks to expand their foreign holdings and diversify business lines and revenue streams. Canadian banks have primarily used foreign funding to support growth in foreign assets.

However, approximately $190 billion (about 7 per cent of total Canadian-dollar bank assets) is converted into Canadian dollars and used to fund lending in Canada. This use of foreign funding has supported lower borrowing costs and contributed to an increase in overall indebtedness in Canada.25 A sharp rise in the cost of foreign funding for Canadian banks, if it occurred, would result in a narrowing of funding options. This could then raise borrowing costs for Canadian banks, with the higher costs in turn likely passed on to households, businesses and institutions.

In an environment of low interest rates, some investors have been taking on more risk to boost returns. In fixed-income markets, this search for yield has been characterized by greater demand for corporate bonds and bonds with longer maturities. It has fostered a rise in the number and size of corporate bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and corporate bond mutual funds.26

Canadian corporate bond mutual funds have grown to around $118 billion in assets under management, from $46 billion at the end of 2007; this represents just over 20 per cent of the total corporate bond market in Canada. Corporate bond ETFs have also grown significantly in Canada over the same period, reaching about $19 billion at the end of 2017.

Both mutual funds and ETFs can be managed actively or passively. Actively managed funds try to outperform benchmarks, whereas passively managed funds typically track the returns of a market index. If investors decided to exit the sector during a period of stress, passive bond funds could mechanically sell corporate bonds to meet investor redemptions. Active bond fund managers have more discretion on how to meet liquidity needs, but they would also likely sell some corporate bonds in addition to their liquid asset holdings.27

Simultaneous portfolio rebalancing across funds during a stress period could amplify declines in asset valuations and market liquidity. There are several mitigating factors, however. A significant share of corporate bonds is held outside of these funds. Further, global and domestic authorities have strengthened regulatory guidance, particularly that related to the funds’ leverage, concentration limits and liquidity management.28 Authorities continue to monitor the risk-management strategies of bond mutual funds and ETFs.

Non-financial corporate debt relative to income has been growing rapidly in recent years.29 Sectoral analysis indicates that the rise in indebtedness has been driven largely by firms in the oil and mining industries (Chart 10a).30

The oil and mining industries combined accounted for around one-fifth of non-financial corporate debt in 2017. The large increase in debt relative to income in these industries reflects both higher debt and a sharp decline in income due to lower commodity prices. Income has recovered somewhat but remains low.

Beyond these two industries, aggregate indebtedness is within ranges typical for the past 20 years. Further, the levels of cash holdings are rising, suggesting that firms have adequate financial flexibility. Even if interest rates return to their long-term average, debt-service ratios will likely remain within historical ranges (Chart 10b). In addition, there is no evidence of an increase in the share of debt held by firms with distressed balance sheets.31

Note: The debt-to-income ratio is defined as debt divided by earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization.

The debt-service ratio (DSR) is defined as interest payments divided by earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization.

Debt includes all interest-bearing borrowings obtained from nonaffiliated companies.

Sources: Statistics Canada Quarterly Financial Statistics for Enterprises and Bank of Canada calculations

Last observation: 2017

Crypto assets are used to transfer value through electronic platforms. Bitcoin is the most well known, but there are more than 1,600 crypto assets with a wide variety of designs and purposes. Although they are sometimes referred to as crypto-currencies, crypto assets do not perform the key functions of money: they are currently quite poor media of exchange, stores of value and units of account.32 Crypto assets are built on a distributed ledger technology that has the potential to bring efficiency benefits to the financial system, but they also pose new risks.

The total worldwide market value of all crypto assets peaked at above $1 trillion at the beginning of 2018 but has declined substantially since.33 This value is small compared with a worldwide equity market capitalization of well over $75 trillion. But the market capitalization of crypto assets grew rapidly through 2017, and the daily transaction volume is now more than 75 times higher than in early 2017, reaching more than $25 billion per day.

Financial institutions participating in the Bank of Canada’s Financial System Survey report negligible investments in crypto assets, either for themselves or their clients.34 But financial institutions could become exposed to crypto assets through their clients’ own activities or through regulated exchanges where derivatives based on crypto assets are traded.

Crypto asset markets are evolving quickly and could have financial stability implications in the future if their size and links to the financial system continue to grow. The markets are largely unregulated in many countries and are characterized by high price volatility, fragile liquidity, and frequent fraud and cyber attacks.

The improvement of anti-money-laundering and anti-terrorist-financing rules continues to be a priority. Authorities have also been moving to strengthen policies related to the effects of crypto assets on consumer and investor protection, market integrity and tax evasion. A coherent and internationally aligned set of policies to control risks stemming from crypto assets is essential.

The Bank is chairing a group at the Financial Stability Board that is monitoring financial innovations, including crypto assets, in the context of assessing financial system vulnerabilities. The Bank also participates in the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision discussions on the implications of crypto assets for the banking system. Canadian authorities are contributing to the G20’s work to mitigate risks posed by crypto assets without discouraging innovation. At a recent G7 meeting, finance ministers and central bank governors agreed that international coordination is needed to ensure that regulatory actions are effective in a globally interconnected financial system. In addition, the Canadian Securities Administrators is providing guidance on the applicability of securities law and warning of risks in these markets.35

Key risks

Table 3 shows the risk scenarios for the Canadian financial system. Its purpose is to identify the most important downside risks rather than all possible negative scenarios. Each risk includes a rating based on Governing Council’s judgment regarding the probability of the risk occurring and the expected severity of the impact on the Canadian financial system. The overall risk to the financial system remains broadly unchanged from the November Report. A new methodology called “GDP at risk” helps assess the impact of financial system risks on the economy (Box 2).

The risk of “stress emanating from China or other emerging-market economies” is no longer presented as a separate risk scenario, as it was in the November 2017 FSR. Instead, financial system stress in China or other EMEs has been incorporated as a potential trigger for risks 1 and 3. This better reflects the indirect transmission channels from risks in China to Canada and does not affect the overall assessment of risks to the Canadian financial system.

The Bank also solicits the views of financial system participants through its Financial System Survey, discussed in a report in this issue. Canadian financial system participants identified the risks of a cyber attack, a geopolitical event and a pronounced decline in property prices as among the most important risks to their firms’ own activities and the broader financial system.

Table 3: Key risks to the stability of the Canadian financial system

| Risk scenarios | Ratings and developments since the November 2017 Financial System Review |

|---|---|

| Risk 1: A severe nationwide recession leading to a rise in financial stress | Elevated but decreasing |

|

|

| Risk 2: A house price correction in overheated markets | Moderate |

|

|

| Risk 3: A sharp increase in long-term interest rates driven by higher global risk premiums | Moderate but increasing |

|

|

| Risk ratings: | Low | Moderate | Elevated | High | Very high |

|---|

Box 2: Introducing GDP at risk

In assessments of financial system risks, considering the range of possible economic outcomes is as important as looking at the most likely path for the economy. Lower interest rates, for example, boost expected economic growth in the short run, but can also lead to a buildup in financial system vulnerabilities by increasing indebtedness. When vulnerabilities in the economy are elevated, adverse shocks can have a larger negative impact on gross domestic product (GDP). For example, if households cannot service their debt when their income falls or financial conditions tighten, larger downside risks to GDP can materialize.

Chart 2-A illustrates how statistical tools can be used to model the impact of increased vulnerabilities, such as indebtedness, on possible outcomes for GDP growth. Greater indebtedness increases median GDP growth, but also amplifies downside risks.

The downside risks to GDP can be summarized using GDP at risk.36 This is a measure of the worst-case scenario for GDP growth: the rate of GDP growth over one year that should be exceeded in all but the worst 5 per cent of possible outcomes (i.e., the fifth percentile of GDP growth). Financial system vulnerabilities make the worst-case outcome for GDP growth even worse.

GDP at risk is influenced by both macroeconomic performance and financial vulnerabilities (Chart 2-B). For example, GDP at risk worsened in 2015, mostly because of the macroeconomic implications of the oil price shock. But in the period since 2016, the growth in household indebtedness and housing market imbalances has weighed on GDP at risk, even while macroeconomic performance has improved.

By constraining vulnerabilities, financial sector policy may improve GDP at risk. For example, recent policy actions are expected to slow the accumulation of household debt and dampen house price growth. These macroprudential policies tend to reduce median GDP growth, but they should also reduce the chances of a severe contraction of GDP, as measured by GDP at risk. Analyzing policy changes in this framework helps in understanding and quantifying economic and financial stability trade-offs.37

Source: Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q4

Assessing financial system resilience

Financial system resilience refers to the system’s capacity to withstand and quickly recover from a wide array of shocks. The Bank of Canada is well placed to conduct an overall assessment of this resilience because of its system-wide perspective and the link between this analysis and its other mandates.38 The Bank provides liquidity to the financial system, oversees payment clearing and settlement systems, and develops and implements monetary policy. This section discusses some of the tools the Bank uses to assess financial system resilience. Although the section focuses on the banking sector, the Bank conducts resilience assessment broadly across the financial system, including non-bank credit intermediation.

Canadian banks maintain strong capital and liquidity buffers. Their regulatory capital and liquidity ratios have been stable over the past year, with the Big Six and smaller banks maintaining healthy buffers over the regulatory minimums (Table 4). The equity capital of the Big Six banks trades at a significant premium to its book value. This reflects market expectations of the future profitability of the banks, which can change quickly in the face of significant financial or economic shocks. Certain smaller banks have market values of equity capital below their book values, reflecting lingering market concerns about their future profitability.

More broadly, participants in the Bank of Canada’s Financial System Survey were asked about their confidence in the Canadian financial system if a large shock were to materialize. Most survey participants remain confident in the current resilience of the financial system.

Table 4: Measures of banking system resilience

| Big Six banks | Smaller banks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2017 | April 2018 | Regulatory minimum | March/April 2017 | March/April 2018 | Regulatory minimum | |

| Common equity Tier 1 capital ratio | 11.2 | 11.4 | 8 | 12.6 | 13.4 | 7 |

| Basel III leverage ratio | 4.2 | 4.3 | 3 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 3 |

| Liquidity Coverage Ratio | 133 | 137 | 100 |

Safeguarding the financial system

The Bank of Canada collaborates with global and domestic authorities to foster a stable and efficient financial system in Canada. This includes measures to increase the resilience of financial institutions and financial market infrastructures and to promote the continuous functioning of core funding markets. In addition to policy measures discussed in the vulnerabilities section in this issue, notable developments have contributed to the efficiency and stability of the broader financial system.

The current core payment systems operated by Payments Canada—the Large Value Transfer System (LVTS) and the Automated Clearing Settlement System (ACSS)—together process nearly all electronic payments that occur among financial institutions in Canada. Actions to modernize these systems to keep up with end-user needs and to adopt the latest technologies are outlined by Payments Canada in its Modernization Target State document.39 The Bank of Canada is involved in this multi-year project as the authority responsible for ensuring that risks are being adequately controlled in core payment systems.

The LVTS will be replaced by Lynx, which will be designed to have the same resiliency characteristics, but with improved ability to support new developments such as liquidity saving mechanisms. Lynx will be a real-time gross settlement system, a framework that has been widely adopted internationally. It will eliminate credit risk among financial institutions, thereby reducing the potential for adverse behaviour by participants during a financial crisis as concerns about other financial institutions arise.

The ACSS will be replaced by the Settlement Optimization Engine, which will continue to process routine and scheduled payments such as cheques, bills and payrolls. The system will be designed with enhanced risk-management functions and improved efficiency of payments processing for financial institutions. A second system called Real-Time Rail is being developed with a focus on new, faster ways to make payments, which facilitates increased competition and fosters innovation. The Bank also intends to consider revisions to its settlement account policy that would broaden access and support these efforts while minimizing risks to the payment system.40

Financial benchmarks are an important part of the financial system architecture, since they are often used to determine the value or payment of a variety of financial contracts.41 Since the global financial crisis, international authorities have taken a number of steps to bolster the integrity of core benchmarks in response to concerns about the governance and robustness of benchmarks.

In conjunction with global efforts, the Canadian Alternative Reference Rate Working Group was formed in March 2018, under the auspices of the Canadian Fixed-Income Forum.42 This group will analyze the need to identify and develop a risk-free term interest rate benchmark to complement the existing Canadian Dollar Offered Rate. The goal is to ensure that benchmarks reflect market conditions and support price discovery within a strong governance framework.

Moving toward ending too-big-to-failImplicit government guarantees create incentives for excessive risk-taking and distort prices and resource allocation, potentially increasing the likelihood of bailouts from taxpayers. Staff analysis estimates that this too-big-to-fail subsidy reduces the cost of borrowing for Canada’s Big Six banks43 by 22 to 26 basis points, equivalent to annual savings of $559 million to $713 million.44

Under a new bank bail-in regime, certain bondholders will be expected to share in the losses incurred in a bank resolution.45 Senior unsecured bonds will be converted into equity to recapitalize a failing bank and help restore its viability. This will reduce the probability of future public bailouts and improve incentives in bank funding markets. The bail-in regime is an important part of a broader recovery and resolution approach that allows the government to credibly commit to not rescue a systemically important bank that is in distress. It will apply to senior obligations of the Big Six Canadian banks and comes into force in September 2018.

Continuing work to increase the use of the repo central counterpartyIn April, the Canadian Derivatives Clearing Corporation launched a new direct-clearing model that enables the most active buy-side participants in the repo market to centrally clear fixed-income and repo transactions as direct central counterparty (CCP) participants. This service will allow a group of public sector pension funds, which account for a substantial part of buy-side activity in the Canadian repo market, to gain direct access to the CCP. The new service enhances the resilience of this core funding market by mitigating counterparty credit risk.46 Since other types of buy-side participants are not eligible for this service, part of the repo market will, for the moment, continue to be settled on a bilateral basis.

Ensuring critical financial market infrastructures operate continuouslyFinancial market infrastructures (FMIs) provide critical payment clearing and settlement services. For the financial system to operate effectively, FMIs that pose systemic or payment system risk must be able to deliver their services regardless of the circumstances. To that end, the Bank of Canada and other financial sector authorities have developed a resolution regime that will preserve financial stability, maintain critical services and minimize public exposure to loss in the highly unlikely event of an FMI failure. The Government of Canada proposed that the Bank be the resolution authority for Canadian FMIs that pose systemic or payment risk. The Bank will coordinate FMI resolution planning with provincial and federal authorities. This important new responsibility is discussed in the report, “Establishing a Resolution Regime for Canada’s Financial Market Infrastructures,” in this issue.

Reports

Establishing a Resolution Regime for Canada’s Financial Market Infrastructures

This report highlights how an effective resolution regime promotes financial stability. It does this by ensuring that financial market infrastructures (FMIs) would be able to continue to provide their critical functions during a period of stress when an FMI’s own recovery measures were failing. The report explains the Bank of Canada’s new role as the resolution authority for FMIs, which will further bolster financial system resilience.

Covered Bonds as a Source of Funding for Banks’ Mortgage Portfolios

The author traces developments in the Canadian covered bond market. Covered bonds could be a valuable way to provide a stable and diverse source of funding, particularly for smaller banks. However, higher issuance could increase banks’ vulnerability to liquidity stress, with implications for the broader financial system. The author argues that these benefits and challenges can be balanced in a well-designed policy framework.

The Bank of Canada’s Financial System Survey

This report presents the details of a new semi-annual survey that will improve the Bank of Canada’s surveillance across the financial system and deepen efforts to engage with financial system participants. The survey collects expert opinions on the risks to and resilience of the Canadian financial system as well as on emerging trends and financial innovations. The report presents an overview of the survey and provides high-level results from the spring 2018 survey.

Endnotes

This report includes data received up to May 31, 2018.

- 1. The risks posed to households by auto loans, especially loans with extended terms, are discussed in Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, “Auto Finance: Market Trends” (March 2016).[←]

- 2. This analysis of auto loans is based on Bank of Canada calculations using data from TransUnion and regulatory filings of Canadian banks. Loans to borrowers with credit scores less than 680 are considered non-prime for this analysis.[←]

- 3. The 2016 changes to the mortgage insurance rules applied, for the first time, the same underwriting rules to low-ratio portfolio-insured mortgages as those that had previously applied only to high-ratio mortgages. This includes a maximum 25-year amortization period.[←]

- 4. See “Final Revised Guideline B-20: Residential Mortgage Underwriting Practices and Procedures” (from the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions), which was published in October 2017. The revisions to the guideline are intended to reinforce a strong and prudent regulatory regime for residential mortgage underwriting in Canada.[←]

- 5. For information on how debt-service ratios are calculated, see Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Calculating GDS/TDS.”[←]

- 6. Other mortgage underwriting criteria, such as credit history, characteristics of the property and the size of the down payment, can also constrain mortgage size. Borrowers could stretch their borrowing capacity by choosing a mortgage with a longer amortization period.[←]

- 7. Current data limitations restrict this analysis to Ontario. Mortgage finance companies are not included in this category because most of their lending is subject to federally mandated mortgage underwriting standards.[←]

- 8. See the April 2018 Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report.[←]

- 9. Some variable-rate mortgages have fixed payments. As interest rates increase, more of the payment is devoted to interest and less to principal. Borrowers with these mortgages are protected from an immediate cash flow shock but will face a higher principal amount when their mortgage comes up for renewal.[←]

- 10. The difference between interest rate risk and renewal risk for mortgages is discussed in O. Bilyk, C. MacDonald and B. Peterson, “Interest Rate and Renewal Risk for Mortgages,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2018-18 (June 2018).[←]

- 11. Full loan-level data are available from regulatory filings of Canadian banks starting only in 2014. Five-year mortgages originated in that year will be up for renewal in 2019.[←]

- 12. Quality-adjusted benchmark prices from the Canadian Real Estate Association MLS Home Price Index are used.[←]

- 13. An analysis of building fees in the Toronto region is available in Altus Group Economic Consulting, Government Charges and Fees on New Homes in the Greater Toronto Area (May 2, 2018), a study prepared for the Building Industry and Land Development Association. See also B. Dachis and V. Thivierge, “Through the Roof: The High Cost of Barriers to Building New Housing in Canadian Municipalities,” C. D. Howe Institute Commentary No. 513 (May 2018).[←]

- 14. The Greater Golden Horseshoe is a region of Southern Ontario encompassing the Greater Toronto Area and surrounding municipalities. It includes around 9 million residents.[←]

- 15. British Columbia also announced a new tax, effective in autumn 2018, on individuals who own homes in British Columbia but do not pay income taxes there.[←]

- 16. Condominium completions dropped to a five-year low of 13,513 units in 2017—8,121 fewer units than the 21,634 units scheduled for delivery at the beginning of the year. For more on this issue, see “Think Construction Is High Now Just Wait…,” Urbanation (March 26, 2018).[←]

- 17. Evidence from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Starts and Completions Survey suggests that the average time it takes to build a condominium in Toronto has expanded from 19 months in 2004 to 29 months in 2017. The longer average construction time can be attributed to factors such as an increase in the average height of condominium buildings, labour shortages and new land-use regulations. In Vancouver, the time to build increased from 17 months to 20 months.[←]

- 18. The Realosophy results are based on data from Urbanation Inc. and are cited in J. Pasalis, A Sticky End: Lessons Learned from Toronto’s 2017 Real Estate Bubble, Realosophy Realty Inc. Brokerage (April 2018). For a related discussion about the new condominium market, see S. Hildebrand and B. Tal, “A Window into the World of Condo Investors,” Urbanation and the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (April 6, 2018).[←]

- 19. See F. Dinis, “Strengthening Our Cyber Defences” (remarks to Payments Canada, Toronto, Ontario, May 9, 2018).[←]

- 20. The Big Six Canadian banks are the Bank of Montreal, Bank of Nova Scotia, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, National Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Canada and Toronto-Dominion Bank.[←]

- 21. See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, “Reducing the Risk of Wholesale Payments Fraud Related to Endpoint Security,” Bank for International Settlements CPMI Paper No. 178 (May 8, 2018).[←]

- 22. See Box 1 in the June 2017 Financial System Review.[←]

- 23. See the report by T. Ahnert, “Covered Bonds as a Source of Funding for Banks’ Mortgage Portfolios,” in this issue.[←]

- 24. Since 2014, there have been three issuances of private-label residential mortgage-backed securities. For background information on the market, see A. Mordel and N. Stephens, “Residential Mortgage Securitization in Canada: A Review,” Bank of Canada Financial System Review (December 2015): 39–48.[←]

- 25. See G. Bruneau, M. Leboeuf and G. Nolin, “Canada’s International Investment Position: Benefits and Potential Vulnerabilities,” Bank of Canada Financial System Review (June 2017): 43–57.[←]

- 26. For more information, see R. Arora, N. Merali and G. Ouellet Leblanc, “Did Canadian Corporate Bond Funds Increase Their Exposures to Risks?” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2018-7 (March 2018).[←]

- 27. An empirical model of this behaviour is described in R. Arora and G. Ouellet Leblanc, “How Do Canadian Corporate Bond Mutual Funds Meet Investor Redemptions?” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2018-14 (May 2018).[←]

- 28. See, for example, Financial Stability Board, “Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Asset Management Activities” (January 12, 2017). In the Canadian context, an example of securities regulations can be found in “OSC Staff Notice 81-727 Report on Staff’s Continuous Disclosure Review of Mutual Fund Practices Relating to Portfolio Liquidity.”[←]

- 29. Growth in non-financial corporate debt has been the main driver of recent increases in Canada’s credit-to-GDP gap. The Bank for International Settlements has pointed to the credit-to-GDP gap as a measure of the potential for stress in the banking system. For further details, see T. Duprey, T. Grieder and D. Hogg, “Recent Evolution of Canada’s Credit-to-GDP Gap: Measurement and Interpretation,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2017-25 (December 2017).[←]

- 30. The real estate, auto leasing and financial services industries are excluded from the analysis.[←]

- 31. T. Grieder and M. Lipsitz, “Measuring Vulnerabilities in the Non-Financial Corporate Sector Using Industry- and Firm-Level Data,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2018-17 (June 2018).[←]

- 32. See C. A. Wilkins, “Financial Stability: Taking Care of Unfinished Business” (remarks at the Rotman School of Management conference, Toronto, Ontario, March 22, 2018); and S. S. Poloz, “Three Things Keeping Me Awake at Night” (remarks at the Canadian Club Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, December 14, 2017).[←]

- 33. Source: coinmarketcap.com. All figures are expressed in Canadian dollars.[←]

- 34. See the report by G. Bédard-Pagé, I. Christensen, S. Kinnear and M. Leboeuf, “The Bank of Canada’s Financial System Survey,” in this issue.[←]

- 35. See “Cryptocurrency Offerings,” CSA Staff Notice 46-307 (August 24, 2017); and “Canadian Securities Regulators Remind Investors of Inherent Risks Associated with Cryptocurrency Futures Contracts,” press release (December 18, 2017). The International Organization of Securities Commissions is also addressing cross-border issues stemming from crypto assets that could affect investor or consumer protection.[←]

- 36. T. Adrian, N. Boyarchenko and D. Giannone, “Vulnerable Growth,” American Economic Review (forthcoming).[←]

- 37. This framework is discussed in T. Duprey and A. Ueberfeldt, “How to Manage Macroeconomic and Financial Stability Risks: A New Framework,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2018-11 (May 2018).[←]

- 38. See D. Lombardi and L. Schembri, “Reinventing the Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability,” Bank of Canada Review (Autumn 2016): 1–11.[←]

- 39. See Payments Canada, Modernization Target State: Summary of the Key Requirements, Conceptual End State, Integrated Work Plan and Benefits of the Modernization Program (December 2017).[←]

- 40. Access policies are discussed in Department of Finance Canada, “Consultation on the Review of the Canadian Payments Act” (May 25, 2018).[←]

- 41. For more on benchmarks in Canada and other key jurisdictions, see T. Thorn and H. Vikstedt, “Reforming Financial Benchmarks: An International Perspective,” Bank of Canada Financial System Review (June 2014): 45–51.[←]

- 42. More information on the working group can be found on the Bank’s website.[←]

- 43. In March 2013, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions designated the Big Six Canadian banks as “domestic systemically important banks.”[←]

- 44. These estimates are based on the ratings uplift determined by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s on the banks’ senior unsecured debt obligations. See P. Palhau Mora, “The ‘Too Big to Fail’ Subsidy in Canada: Some Estimates,” Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper No. 2018-9 (February 2018), for a comprehensive discussion of the too-big-to-fail issue and estimates of implicit subsidies in Canada.[←]

- 45. See Department of Finance Canada, “Government of Canada Adopts Regulations to Support a Sound and Resilient Financial System” (April 18, 2018).[←]

- 46. The systemic risk-management benefits of central clearing for this market are discussed in P. Chatterjee, L. Embree and P. Youngman, “Reducing Systemic Risk: Canada’s New Central Counterparty for the Fixed-Income Market,” Bank of Canada Financial System Review (June 2012): 43–49. The benefits of expanded direct clearing are discussed in A. Côté, “Toward a Stronger Financial Market Infrastructure for Canada: Taking Stock” (remarks to the Association for Financial Professionals of Canada, Montreal Chapter, Montréal, Quebec, March 26, 2013).[←]